Watch Jonathan's experience

Sensory alterations and weight loss in cancer

Alterations in taste and smell are a common side effect of cancer treatment1 and can increase patients’ risk of weight loss and malnutrition1-6. Read on to learn about types of sensory alterations, how they can cause weight loss and malnutrition, and discover how sensory-adapted oral nutritional supplements (ONS) can support patients.

How common are sensory alterations in patients with cancer?

Taste and smell alterations are common in patients with all types of cancer. Sensory changes have been reported prior to cancer diagnosis, during, and up to 1 year after treatment for cancer1. Taste and smell changes are typically exacerbated during treatment, with a prevalence of 16–70% during chemotherapy and 50–70% during radiotherapy1.

What type of sensory alterations do cancer patients experience?

Taste and smell changes are typical sensory alterations associated with cancer and can vary widely in their characteristics and impact on patients7. Chemosensory alterations may include hypo- or hypersensitivity to taste or smells, distortion of taste (dysgeusia), or taste perception in the absence of a stimulus (phantogeusia)7,8. Dysgeusia and the development of bad tastes – such as bitter, chemical, metallic, or nauseating – are considered the most common sensory alterations in cancer. For example, a metallic taste was reported by 32% of patients with various cancer types undergoing chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy;4 and by 16% of patients with lung cancer in a separate study9.

What causes sensory alterations in patients with cancer?

The causes of sensory changes in patients with cancer are multifactorial and the underlying mechanisms are not yet fully understood. Most commonly, taste and smell changes occur as a side effect of cancer treatment. Radiotherapy and chemotherapy target rapidly dividing cells, such as taste and smell receptors (and their progenitor/stem cells), thereby causing cytotoxic damage. These therapies may also disrupt the production of saliva and mucus, indirectly affecting taste by causing a dry mouth and oral mucositis1,10. Sensory changes may also arise as part of the complex pathophysiology of cancer. Potential mechanisms include systemic inflammation; modification of the gut microbiota; mechanical obstruction of chemoreceptor sites; tumor interference with neural transmission; and metabolic changes1,10.

Why is it important to address taste alterations?

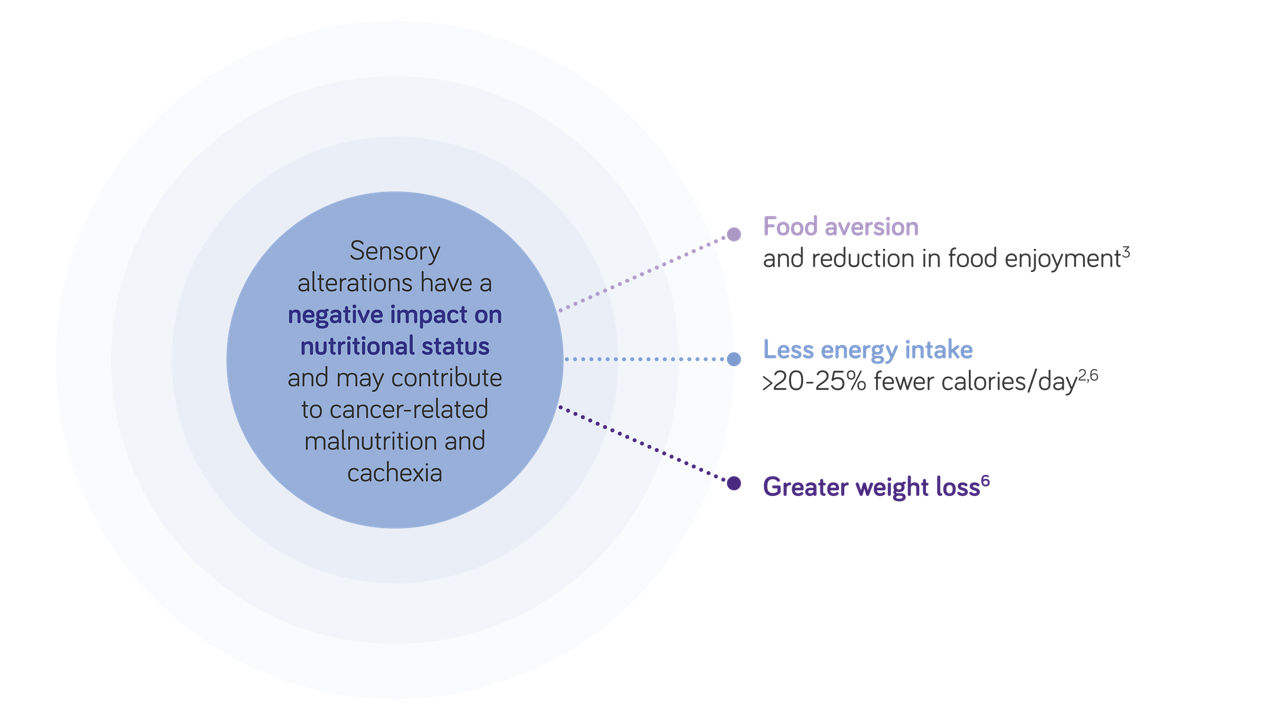

Taste and sensory alterations are an underestimated and distressing side effect of cancer treatment and can have a range of medical and psychosocial consequences. Most significantly, sensory changes may lead to weight loss and malnutrition2,6. Sensory alterations are also associated with worse social-emotional function, emotional and role function, physical function, and poor overall quality of life11,12.

What causes taste changes in cancer?

You perceive flavor via around 5000 taste buds on your tongue and inside your mouth. The taste buds contain special cells, called receptors, which detect the basic tastes of sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami2,3. Sometimes, taste changes are caused by the cancer itself interfering with the body’s normal processes2,3. More often, however, taste changes are an unintended side effect of cancer treatment. Both radiotherapy and chemotherapy damage the tastebuds, affecting how food and drink taste; they can also affect the sensory nerves, changing how things feel in the mouth2,3. Surgery for cancer may also affect taste and smell if it involves damaging parts of the mouth, tongue, or nose.

Why can cancer cause a dry mouth?

Treatments for cancer – particularly chemotherapy and radiotherapy – can cause a dry mouth by reducing the amount of saliva you make. Because saliva helps the tastebuds to perceive flavor, having a dry mouth can affect your sense of taste. It can also cause other problems, such as mouth infections, a sore throat, and even tooth decay2,3.

How can taste alterations increase the risk of malnutrition?

Sensory changes can give rise to eating problems – such as food aversion and reduced food diversity – as well as decreasing patients’ adherence to nutritional interventions13-16. Patients with taste changes often have a diminished appetite and a reduced energy and nutrient intake; this can adversely affect their nutritional status and lead to weight loss2-7,17.

In a study of patients with advanced cancer undergoing chemotherapy, patients with sensory alterations consumed 20–25% fewer calories per day and their average 6-month weight loss increased proportionally to the severity of chemosensory alterations2. Weight loss rose from 4.3% in patients without taste or smell alterations to 5.5%, 9.0%, and 12.3% in patients who were mildly, moderately, and severely affected, respectively2.

What are the consequences of weight loss in oncology patients?

Weight loss is of particular concern in patients with cancer, since malnutrition, and cachexia are all predictors of poor clinical outcomes. Malnutrition is associated with increased morbidity and mortality, a greater risk of complications, reduced tolerance to chemo- and radiotherapy, and impaired quality of life18,19. For these reasons, it is imperative to address early signs of malnutrition in patients with cancer and to provide optimal nutritional support.

When should nutritional support and ONS be used?

In patients with or at risk of cancer-related malnutrition who are able to eat, the European Society of Clinical Oncology (ESMO) recommends dietary counselling as the first choice of nutritional support to improve oral intake and encourage weight gain20. Dietary counselling should be provided by a trained professional and should emphasise protein intake, an increased number of meals per day, treatment of secondary nutrition impact symptoms with nutritional supplements offered when necessary. The ESMO guideline also recommends that oral nutritional supplements (ONS) can be used as part of dietary counselling to improve energy intake and induce weight gain, if oral intake from a normal diet is insufficient. Click to read the full ESMO guidelines on managing cancer-related cachexia20.

Why is it important to consider sensory alterations when prescribing ONS?

The success of ONS at improving nutritional status and clinical outcomes is dependent on patient compliance21,22. But achieving full compliance with ONS can be challenging if chemosensory changes are making certain flavors and textures unappealing or even unpalatable. Acceptability and liking of ONS are important factors in patient compliance with supplements23,24; optimizing the palatability and acceptability of ONS is therefore an important strategy to improve patient compliance and maximize the success of ONS.

- Spotten LE, et al. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:969-84.

- Brisbois TD, et al. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41:673-83.

- Boltong A, et al. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:2765-74.

- McGreevy J, et al. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:2635-44.

- Turcott JG, et al. Nutr Cancer. 2016;68:241-9.

- Belqaid K, et al. Acta Oncol 2014;53:1405-12.

- Drareni K, et al. Semin Oncol. 2019;46:160-72.

- Hummel T, et al. GMS Curr Top Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;10:Doc04,

- Sarhill N, et al. Support Care Cancer. 2003;11:652-9.

- Murtaza B, et al. Front Physiol. 2017;8:134.

- Alvarez-Camacho M, et al. Qual Life Res. 2016;25:1495-504.

- de Vries YC, et al. Supportive Care Cancer. 2016;24:3119-26.

- Ravasco P. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2005;9 Suppl 2:S84-S91.

- Coa KI, et al. Nutr Cancer. 2015;67:339-53.

- van Bokhorst-de van der Schueren MA, et al. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2005;9Suppl 2:S74-83.

- Skolin I, et al. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14:369-78.

- Bressan V, et al. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25:1699-712.

- Ryan AM, et al. Nutrition 2019;67-68:110539.

- Van Cutsem E, Arends J. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2005;9 Suppl 2:S51-63

- Arends J, et al. ESMO Open. 2021;6:100092.

- Hubbart et al. 2012 Clin Nutr 31(3):293-312

- De van der Schueren et al. Ann Oncol. 2019;29(5):1141-53

- Lidoriki I, et al. J Am Coll Nutr. 2020;39:650-6.

- Hogan SE, et al. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27:1853-60.

- Ryan et al. Proc Nutr Soc. 2016;75(2):199-211.

- Fearon K et al. Lancet Oncol, 2011;12(5):489-95.

- Capuano G, et al. Head Neck 2008;30:503-8.

- Andreyev HJ, et al. Eur J Cancer, 1998;34:503-9.

- Rickard KA, et al. Cancer 1983;52:587-98.

- Andreyev HJ et al. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34(4)p.503-9.

- Prado CM, et al. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol, 2011; 67(1): p.93-101.

- Fearon KC. Eur J Cancer 2008;44(8): p.1124-32.

Are you a healthcare professional or (carer of) a diagnosed patient?

The product information for this area of specialization is intended for healthcare professionals or (carers of) diagnosed patients only, as these products are for use under healthcare professional supervision.

Please click ‘Yes’ if you are a healthcare professional or (carer of) a diagnosed patient, or ‘No’ to be taken to a full list of our products.

The information on this page is intended for healthcare professionals only.

If you aren't a healthcare professional, you can visit the page with general information, by clicking 'I'm not a healthcare professional' below.